Massachusetts-based artist Chris Hill focuses on creating impressively scaled acrylic paintings of the natural world. Leveraging vivid detail to explore the connections between plants and pollinators against the backdrop of a country where industrial farming is the norm, he makes important observations in his work. Chris was previously featured in one of my virtual exhibitions, and recently I took part in a conversation with him to explore his work and process.

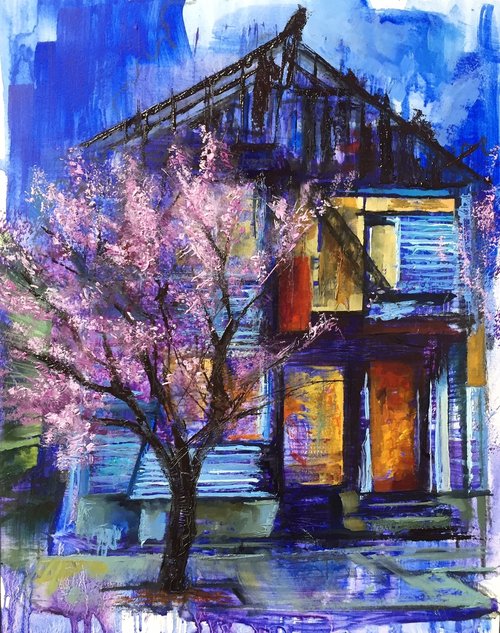

Chris Hill, Before the Spotted Lanternfly, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 60” x 48” (Image courtesy of the artist)

Can you talk a bit about your interest in the natural world and what parts of your background led you to make your Nocturnal Landscapes series?

When I was growing up my favorite hobbies were abstract painting, identifying plants and insects, and walking in the woods. So, when I began to focus on realism, plants and insects were natural subjects for me. Later during my work selling fertilizer I saw many different farms and I was inspired to paint the few that were environmentally friendly.

How do you get started on these paintings? Are you working from nature, from photographs, or a combination thereof?

I compose my scenes from a combination of drawings done in the field and photographs of individual plants and insects. Starting with a black canvas and then the sky, the ground, and then the farthest subjects. The insects are the final layer after all the larger subjects are arranged.

Do you consider your paintings to fall into the genre of scientific illustrations, or are they more expressive than that?

I do strive for accuracy in the anatomy of my paintings, but I wouldn’t say they are scientific illustrations. Sometimes I adjust color, scale and relative perspective as needed. I am more concerned with capturing the spirit of the plant than I am with capturing it’s exact physiology.

Why is the nocturnal element of the landscape important to you?

When I began the Nocturnal Landscapes series, I was living in the middle of a giant, toxic, potato field. The field was sprayed heavily with pesticides, and it was done at night so fewer people were exposed to the clouds of chemicals. So, I began to imagine what the farm might look like at night if it were a healthy ecosystem instead.

How do these paintings interact with other elements of your practice as an artist, or do they?

In addition to working as a carpenter, I enjoy practicing a few different art forms and hobbies, including metal sculpture, writing, gardening, wine making etc. However, I’ve always focused on acrylic canvas painting with a special, crazy obsession. I allow it vastly more time and effort than any other medium. I think it is important to specialize if you want to really master something.

What do you hope viewers experience when looking at this work?

I want my audience to empathize with the natural world; to feel how complex it is, to feel how delicate it is, and to feel how inextricably connected we are to it.

What is next for you in this series, and how do you expect to build on the ideas you're exploring?

There is infinite inspiration to be found in nature. I’m working on portraying flight, plants swaying in the breeze, atmosphere, and dew among other things. Nature is never static. I’m always looking for new ways to capture motion and growth.

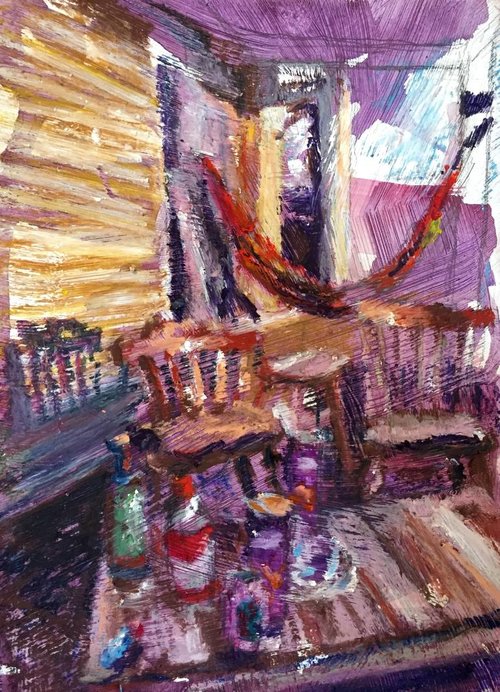

Learn more about Chris and his work at www.nocturnallandscapes.com and follow his studio on Instagram via @nocturnallandscapes. Peruse samples of his work below, and click each image for a full view of his paintings.