Through August 28, an exhibition at the Attleboro Arts Museum explores the remarkable variety one can find within the work of just eight artists. The show, titled 8 Visions, features photographic collages by Monica DeSalvo, drawings by Craig Elliott, ceramics by Lindsey Epstein, textile-based work by Virginia Mahoney, paintings by Kat Masella and Alexander Morris, photographs by Lisa Redburn and jewelry by Chuck Tramontana. The process for selecting these eight artists began with sixty applications, first juried down to twenty finalists by Jennifer Jean Okumura, with exhibitors selected by Anne Corso and Lauren Riviello. The result is an impressive group that speaks to the richness of style and technique that can be found in the New England art community.

The show is wonderfully varied and viewers will find captivating details around every corner of the museum’s generous gallery located in the heart of downtown Attleboro. Across a spectrum of media, the exhibition brings out the individuality of the featured artists. The connecting thread is often a distinct interest in texture and surface, be it real or illusion. Particular standouts in the exhibition include the highly tactile drawings and paintings of Craig Elliott and Alexander Morris, the poignant mixed media works of Monica DeSalvo, and quiet photographic triptychs executed by Lisa Redburn.

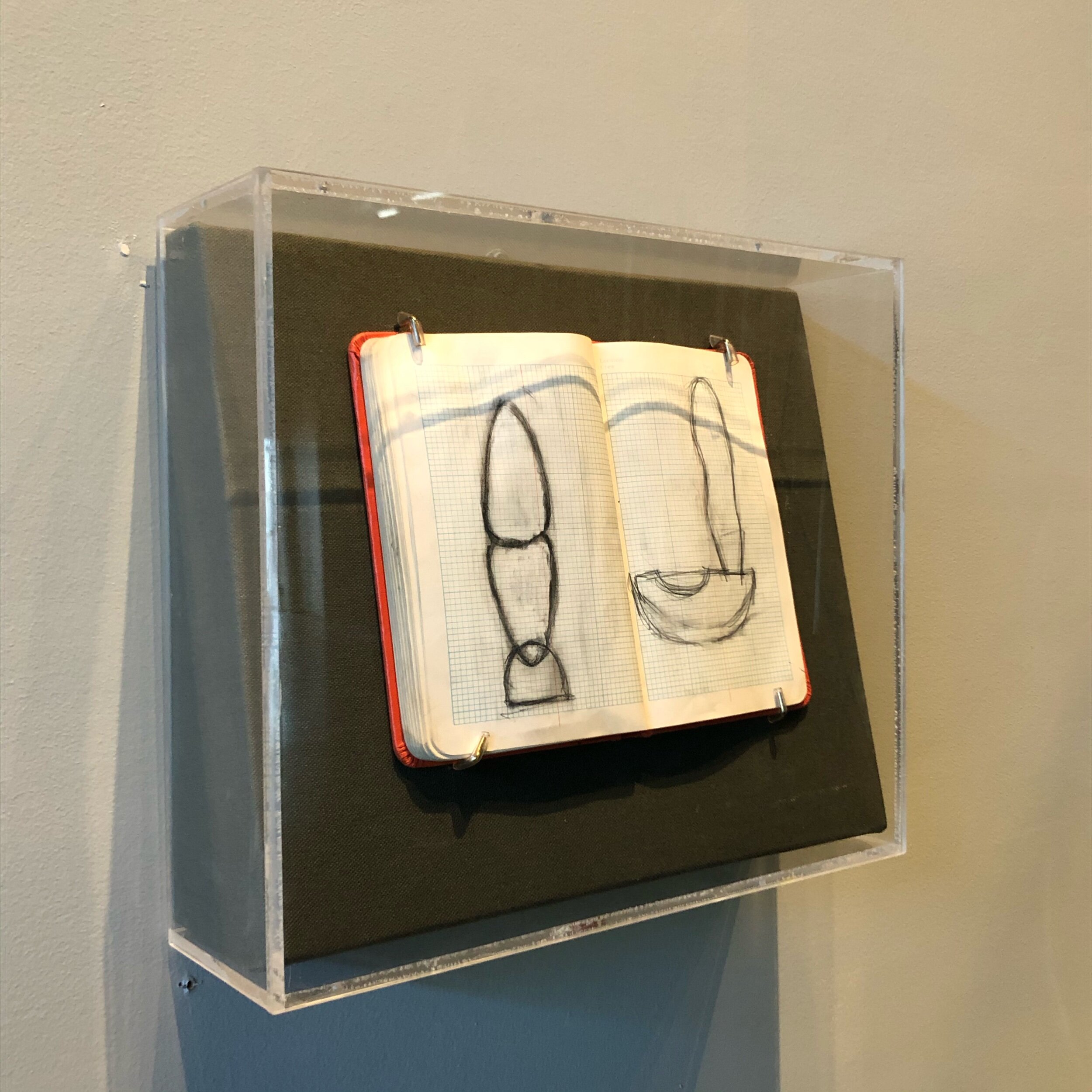

Craig Elliott, an artist who trained as an architect, exhibits a series of charcoal drawings undergirded with thoughtful design. Included in the exhibition, one finds a collection of diminutive preparatory sketches for Totemic, one of Elliott’s large scale drawings. This gives a deep sense of the artist’s knack for craftsmanship and informs a better appreciation for the completed works on view. The little drawings, though preliminary, are actually quite exquisite and hold their own against the more “finished” works on offer.

A wall of Craig Elliott’s large charcoal drawings invites close inspection.

When looking closely at the surfaces of Elliott’s images, one can find folds in the underlying paper layered over with shadowy details that have a sculptural sensibility. Elliott’s artworks elevate charcoal, often considered an elementary medium, bringing it to the same level as painting. Once completed, the artist’s intricate drawings are varnished. This technique has the effect of coalescing the surfaces of his images into velvety and satisfying wholes.

The painter Alexander Morris, originally from Utah and now based in Rhode Island, is exhibiting a collection of highly textured works that include, among other details, great use of mysterious calligraphic line. Morris’ paintings in the exhibition are tall and columnular, a scale and format which takes on an almost architectural significance. One can return to his work again and again, constantly finding new details. It is tempting to puzzle out how exactly Morris has applied his paints but the weathered quality of his work tends to hold its secrets even to the sophisticated observer.

Like Elliott, Morris has a smaller study included in the exhibition. Although tiny by comparison to his wall-height paintings nearby, Crow’s Nest has an equal compositional power that is impressive and merits admiration.

Wall-height paintings by Alexander Morris are rich in weathered textures.

Monica DeSalvo’s contributions to 8 Visions are deeply personal and unravel issues related to her care of her late father, who experienced dementia. In layered artworks that collage and enhance photography and found objects, DeSalvo excavates her father’s archive, unearthing materials that she combines with imagery to evoke his own words near the end of his life.

An accordion book titled What Do You Think About When You’re Not Sleeping? brings a wonderful dimensionality and duality to the experience of DeSalvo’s work, which will be impactful for the many viewers who have experienced dementia first-hand in their own families.

An accordion book by Monica DeSalvo stands out alongside her two-dimensional collages.

Some of the textural complexity found in artworks on view is captured with great sensitivity by a camera lens, rather than by pencil, pen, or brush. In alluring triptychs, Lisa Redburn utilizes a well-known historical template to honor nature. While the format with which she frames her images echoes tiny altarpieces, Redburn’s subject matter is bright and botanical. In her photographs, one finds a certain meditative quality that can also be found in the solace of the natural world, on a hike, or in a garden. They are beautiful photographs with a hint of Transcendentalism.

A collection of Lisa Redburn’s triptych photographs paired with ceramics by Lindsey Epstein.

While Redburn, DeSalvo, Morris, and Elliott have some of the strongest works on view, all of the participating artists should be lauded for the aesthetic verdancy of their contributions to this delightful show. 8 Visions is a thoughtfully assembled exhibition that invites visitors to relish in an exciting variety of art-making by talented creators living and working in New England today.

8 Visions is on view at the Attleboro Arts Museum through August 28, 2021. The Museum is open Tuesday through Saturday, 10am - 4pm each day. Masks are required for all visitors regardless of vaccination status and admission is a suggested $3 donation. Learn more at www.attleboroartsmuseum.org.