Recently a set of memes highlighting the comic appropriateness of Edward Hopper’s work in our new reality of social distancing have been making the rounds online. The first shows Hopper’s seminal work, Nighthawks, one of the most recognizable images in American art; except in lieu of the few patrons in the original, the space is totally vacant. The second illustrates a collection of Hopper’s paintings of lone figures staring out windows with a pithy line something along the lines of “we are all characters in Edward Hopper paintings now”.

As unease and anxiety sweep the world alongside the rising COVID-19 pandemic, viewers are suddenly reappraising the isolated bodies depicted in so many of Hopper’s paintings. Audiences are beginning to see themselves again in the pale sadness of Hopper’s protagonists, and decades old artworks are taking on new and unexpected meanings.

Edward Hopper’s oeuvre is full of spartanly populated spaces in the heart of normally bustling cities; a girl dining alone in a late night restaurant, a pensive usher in a theater, a man and woman working silently in an office, an empty street, a storefront. Looking at these images now, and knowing what we know about government-mandated separation from our colleagues, our friends, our families and loved ones, they transform into something different. In light of current events, Hopper’s paintings of urban isolation become perceptibly more relevant and more poetic to people living nearly a century later.

Edward Hopper, Automat, 1927, collection of The Des Moines Art Center, Iowa

In Automat, from 1927, a young woman sits staring into a cup of coffee set against the vast black chasm of an unbroken plate glass window which faces a lightless street. Punctuating the halo of darkness is the reflection of two rows of lights that recede behind the viewer into the restaurant. No other patrons are visible; it’s just a woman and her cup of coffee. One of her hands is still gloved, as if she just entered this space from the chilly unseen street beyond. She is heavily draped in a green coat, but below the table, we see her bare crossed legs.

In a normally social space, and at a table with two chairs, a diner sits alone. This image might seem strange and there has always been a persistent weirdness to Hopper’s work - a kind of understandable surreality. For viewers today, this kind of surreality is now all too real and we are all living it. Social interactions are banned and tables of two have been reduced to tables of one.

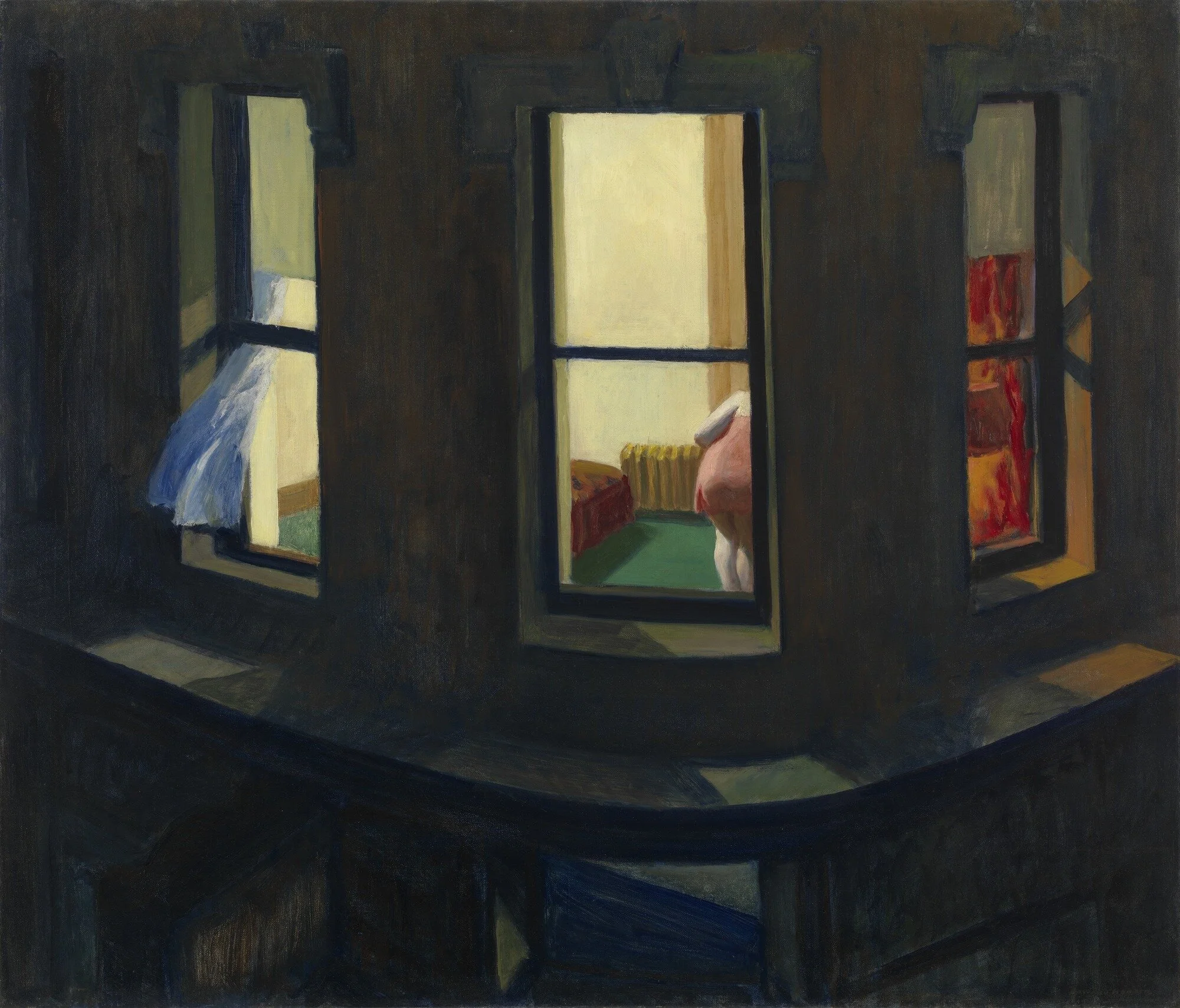

Edward Hopper, Night Windows, 1928, collection of the Museum of Modern Art

A year after Automat, Hopper painted another lone female character this time seen in a glancing moment probably viewed from a passing elevated train. We see a tripartite grouping of windows on the rounded corner of a building. At the right, the warm glow of a shaded lamp illuminates a red curtain. In the left, a white curtain is blowing out the open window. In the center we see just part of the figure, leaned away from us and taking part in some obscured activity. She wears a pink slip and the pale Rembrandt-like flesh of her arm and legs are made all the more glaring by the darkness of the structure’s exterior.

Historically, this image has been viewed as a meditation on the type of voyeurism that can easily occur in a city and also as an examination of the duality of urban life. It is an observance of the closeness in which people live with one another and also the existential distance they have from one another.

In cities like New York, where current issues of distance take on a level of actual practical difficulty, this unique relationship of people to one another within space has become starkly clear. Looking at Night Windows now, it becomes more about separation of space and diminution of physical proximity.

Edward Hopper, New York Movie, 1939, collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

New York Movie, a painting from 1939 which has been in MoMA’s collection since 1941, shows a uniformed theater usher leaning against a wall for a moment of introspection out of view of the few patrons watching a film. In a pool of light cast by a shaded fixture, she leans her head on her hand, supporting her elbow with the flashlight she uses to guide moviegoers to their seats. She closes her eyes just for a moment. The architectural column and wall running down the center of the image form a compositional device to divide the woman on the left from the couple of individuals seated at right. Each of the three characters inhabits their own world within shared space. They are all alone, together.

As movie theaters and other gathering places close, Hopper’s theater takes on a new sense of romance. Places taken for granted in the seventy years since this image was painted are at once precious and missed. And the usher, the type of worker who labors with the public is newly seen by a contemporary audience. People once taken for granted are now essential.

The relationship between service workers, cashiers, custodians and the public is also now more tense and more uncertain. Physical barriers, like the wall in this image, are reconsidered and become vitally important in distancing people from one another. Now, rather than merely benign objects of happenstance, such dividers are seen as necessary safeguards of personal space.

Edward Hopper, Office in A Small City, 1953, collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In a later work from 1953, Hopper returns again to the subject of the lone figure - this time a man, at a desk staring out a window in Office in a Small City. We see the man externally through a window with crystal clarity. He places his palm on his desk and stares out over the rooftops of a neighboring building which has much more detail, charm, and warmth than the battleship gray facade of his own workplace. Jo Hopper said of the painting that it was an image of “a man in a concrete wall”. That is to say it’s an image of a figure trapped inside the circumstances of his life.

In some regards looking at this today there might be a feeling of jealousy. Oh, to be liberated from the confines of one’s home in favor of an office! But there is also a sense of oneness with the character. We are all looking out the same window, alienated from our surroundings and neighbors.

Edward Hopper, Early Sunday Morning, 1930, collection of The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Hopper created many iconic images and one of his most recognizable is Early Sunday Morning, a painting completed at the peak of his production in 1930. In it, the variegated surfaces of 7th Avenue facades are at once representational and abstract. The sunlight of dawn casts long unbroken shadows from hanging signs for tailors and barber shops across the windows of closed storefronts. The city, a place normally defined by people, by crowds, by what Walt Whitman called “the glorious jam”, is desolate. It is reduced to architectural and geometric forms - to a picture plane. The peoplelessness of Hopper’s 7th Avenue isn’t just a metaphor for the brooding urban isolation of his time, but also for the physical realities of our own. Looking at the painting in 2020, it becomes less conceptual and more illustrative. It looks like our neighborhoods now look on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays.

In John Patrick Shanley’s 2005 Pulitzer Prize winning play Doubt: A Parable, the playwright inserts the memorable line “doubt can be a bond as powerful and sustaining as certainty.” The same can be said of our current state of affairs. We are all bound together by doubts, uncertainties, and anxieties. And when we look at Hopper’s protagonists, it is understandable to see much of the same and to feel a new connection to these old pictures.

In a world seemingly much more connected and social than that of twentieth century New York, we are newly aware of isolation and separateness.

So, what can art like Hopper’s provide for us in times of uncertainty, anxiety, and fear? What do these paintings matter? If nothing else, there is something to be said for the reassuring stability of art across time. After all, as they say, art is long, life is brief. Most art, be it the great, the good, or the terrible, will outlast us and for that reason it innately has a tendency to give us something as precious as it is rare: perspective.

Now when we look at Hopper’s paintings we are less likely to see characters that we feel estranged from on the basis of their singularity, but individuals that we feel increasingly more connected to and understanding of. Hopper’s paintings of lone bodies have now become objects of empathic emotion in ways unlike before.

All at once Hopper’s distant, lone characters are knowable and recognizable. That’s because they’re us.