Anyone who has studied art history can attest that much of the work included in major textbooks and courses is still dominated by men. The project to bring stories of women artists to light has been going on in earnest since the mid twentieth century and there are many scholars and organizations contributing to this important work. One such endeavor is Art Herstory, the brainchild of Erika Gaffney. She brings to light work by women artists on multiple platforms - from stationary dedicated to historical makers, to social media posts that buoy contemporary women artists. Erika earned a BA from St. John’s College and pairs her work on Art Herstory with a career in publishing. I had a conversation with her about the work she is doing.

Can you share some of your personal and educational background? How do you come to the work you are doing?

Art Herstory Founder Erika Gaffney

My BA is in Liberal Arts, and I am an acquisitions editor in scholarly publishing, working mostly on books to do with early modern studies and/or art history. Art Herstory has flowed naturally from my job: there are many scholars in my network who work on early modern women, including some who study women artists, specifically. And my work in art history publishing ensures that I am comfortable navigating permissions issues.

How did Art Herstory get started and what is the goal of the project?

In Fall 2017, I was inspired to send a “real” (paper) birthday card to a feminist art historian friend. I wanted to send a card featuring a painting by a Renaissance woman; but it took a long time to find one. The lack of availability of cards reproducing works by historic women artists really bothered me. Art Herstory began with the goal of supplying such cards. But it grew organically—the project does seem to have a mind of its own!—to support the movement to recover the names, works and stories of history’s women artists accessible to today’s art-loving public.

How do you think sharing stories of these women artists shifts perceptions or changes the history of art?

My favorite answer to this question must be credited to historian Merry Wiesner-Hanks, the author of the very first Art Herstory guest post. In Why Do Old Mistresses Matter Today?, she writes, “… a failure to take female Old Masters into account leaves us with a short view, which impoverishes the question and limits our understanding.” It is important to remember that many of the women who almost vanished from art history were not only talented, they were famous in their time. Their work was sought after by kings and popes! How can we gain a full and balanced understanding of our art historical heritage, when whole segments are erased, and on completely arbitrary grounds?

Can you talk about the role of note cards in the work you are doing?

One idea behind the note cards was to invest historic women artists with the trappings of success, in a sense. Another was to use note cards to expose historic women artists to an audience of art-lovers who, if only they had the chance, would love to learn about women artists who have been hidden in the shadows of history. Unfortunately, historic women artists as a theme doesn’t seem compelling enough for museum shops to carry such cards year round. But happily, these days more and more museums are hosting temporary exhibitions about female makers, and some museum shops have at least sold Art Herstory cards in support of such shows.

Art Herstory stationery on display

Does the work of Art Herstory go beyond Old Masters?

Oh yes! While Art Herstory note cards are limited to Old Masters, at least for now, Art Herstory holiday cards reproduce art by women from later periods. For blog post topics, the only restriction is that the artist be deceased—admittedly it is an arbitrary limitation, but Art Herstory is a one-person, volunteer operation and I had to draw the line somewhere. And women of all periods feature in Art Herstory social media posts; in the quarterly “new books about women artists” round ups; and in most segments of the monthly newsletter.

What is something you have learned in the process of coordinating Art Herstory?

I’ve learned so much—about women artists and art history, but also about more practical matters. Managing the blog on the website, I’ve learned (to an extent from my college-age daughter) about search engine optimization and readability scores. I’ve learned how to post new products, run an Etsy store, generate a presence on social media, and ship orders from my home. I’m still trying to get up to speed on the best way to work with museum- and bookstore buyers. To give just three examples of things I’ve learned in an art history context: I’ve discovered that a much larger percentage than I would have imagined of botanical artists are—and were—female. I know more now about saints’ attributes than I would ever have imagined. And very specifically: I learned that in their time, flower painter Rachel Ruysch enjoyed far more commercial success than Rembrandt!

What has the feedback been from people who have interacted with Art Herstory?

The people I’ve heard from—by email, or on social media—are grateful to have access, in some cases at long last, to information about women’s artistic achievements throughout history. Some people—of all genders, from multiple cultures and backgrounds—are sad, sometimes even outraged, that women were largely absent from their high school and college textbooks and lectures. And in terms of products, overwhelmingly customers have expressed appreciation for the quality of the cards, as well as for the idea behind them.

How can people support the work you are doing?

Here are some ideas:

Buy cards! They truly are high quality stationery products, and they make a unique gift. Revenues help to offset the project’s considerable expenses. Readers can shop online at the shop on the Art Herstory website and/or from the Etsy store.

Follow along on social media: Art Herstory is on Instagram, Facebook, Bluesky, and (at least for now) X.

Subscribe to the (free) monthly newsletter: go to the landing page, scroll all the way down, and enter your name and email address into the short form at the bottom of the page.

Propose new products: what kinds of items do you purchase regularly, on which you’d like to see art by historic women?

Read Art Herstory blog posts, contribute guest posts, and/or write comments on posts by other writers.

Spread the word about Art Herstory – on social media, among friends, or (for teachers at all levels) within the classroom!

What is next for Art Herstory and for you?

For me, I will continue to publish books about women artists, as well as blog posts—my Art Herstory work integrates seamlessly into my work on the book series Illuminating Women Artists. For Art Herstory, I’d like to produce more in the way of non-card products. I’m contemplating a monthly wall calendar, themed around one or more historic female artists. But, not in a position to fund such a project on spec, I might launch a Kickstarter campaign.

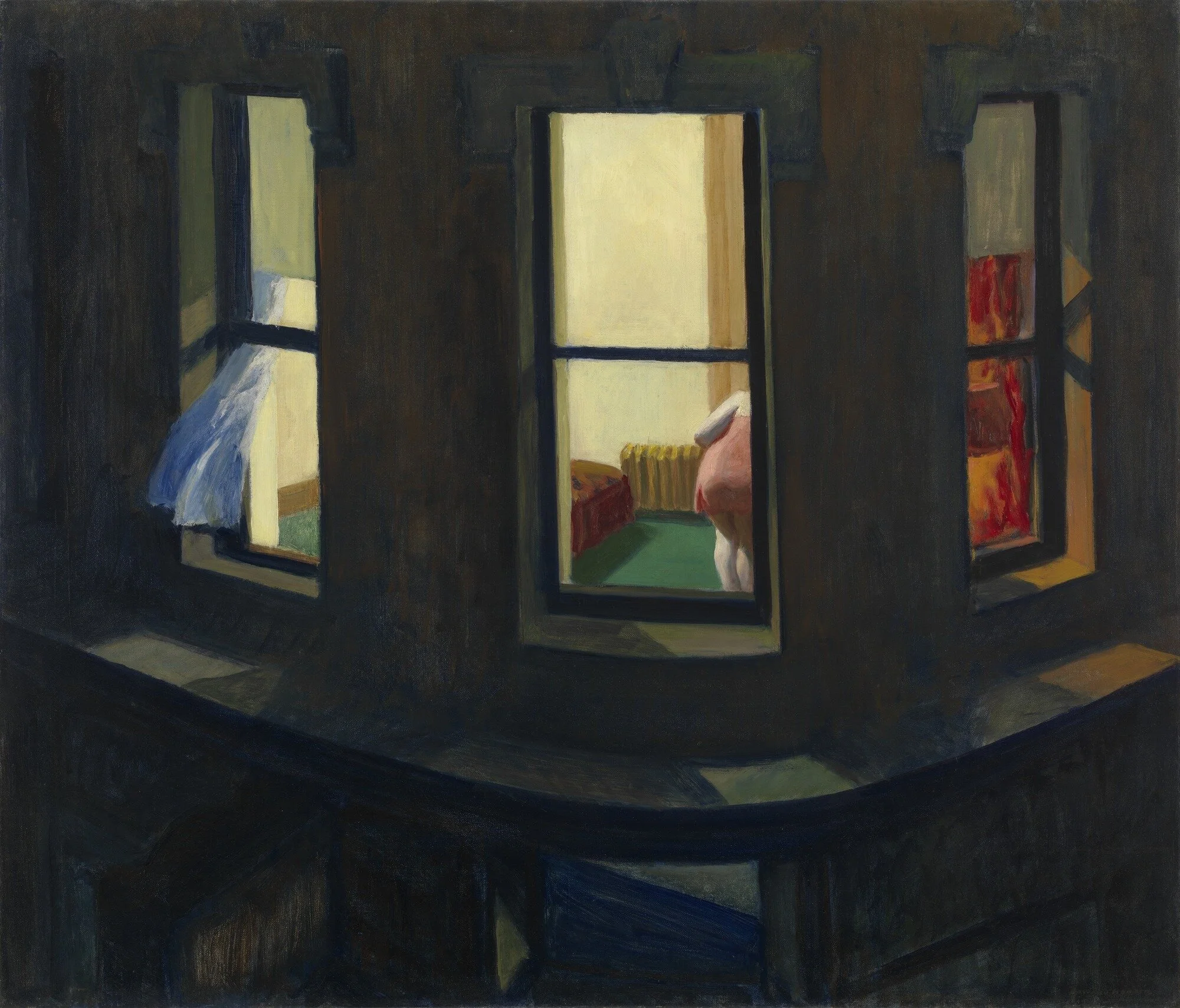

A collection of images by women artists used for holiday cards by Art Herstory