Even for those who frequent art museums, the daily routines of museum guards can be enigmatic. In uniform in the corner of galleries, guards are responsible for the difficult task of keeping priceless artworks safe from hoards of curious onlookers. In his celebrated 2023 memoir All the Beauty in the World, author Patrick Bringley shares insights about art and life from the perspective of a museum guard. The result is a text that makes readers reconsider the art workers who safeguard cultural treasures and provides a new appreciation for how to look closely at works of art.

A former guard at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Bringley came to a profession in security after working in the events department at The New Yorker. The career change was triggered by the passing of his brother from cancer at a young age. In the ensuing years of guarding and looking closely at centuries of human creativity on view at The Met, Bringley found solace and learned about the power of beauty to uplift the human spirit. In his book he movingly explores what he learned and how it changed his life. There are lessons in his story for those who have experienced grief and who might in turn find meaning from encountering art in the aftermath.

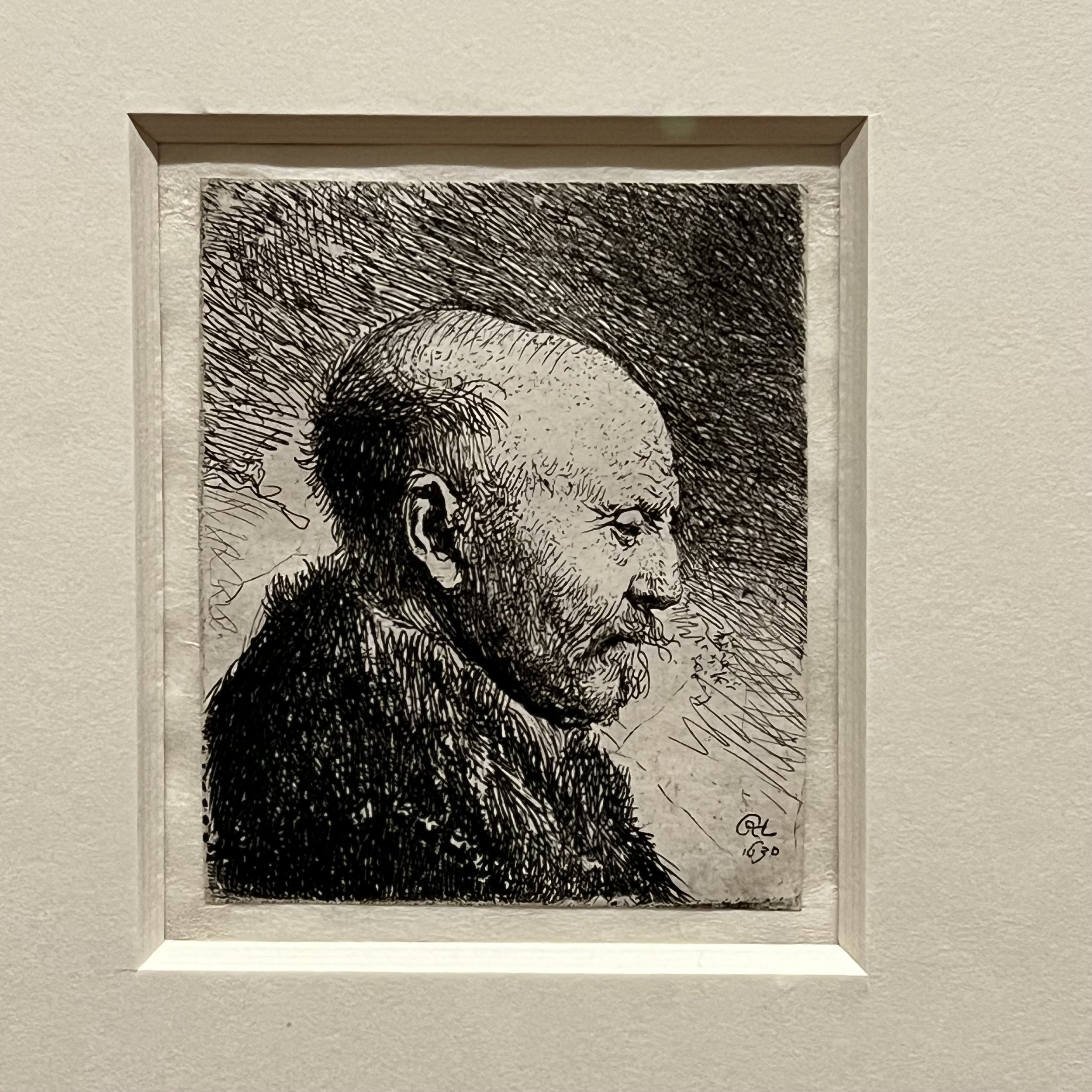

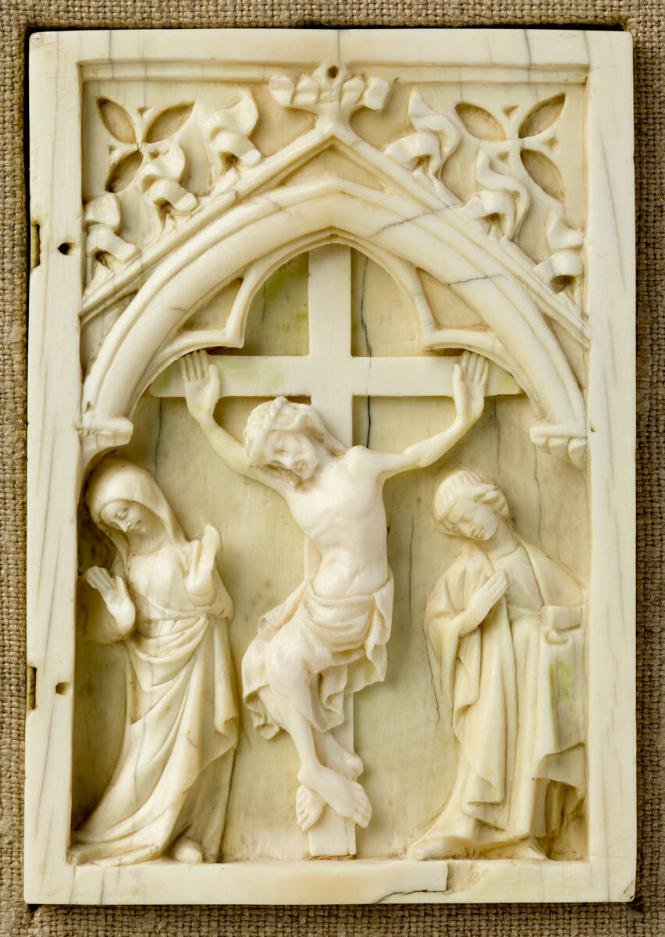

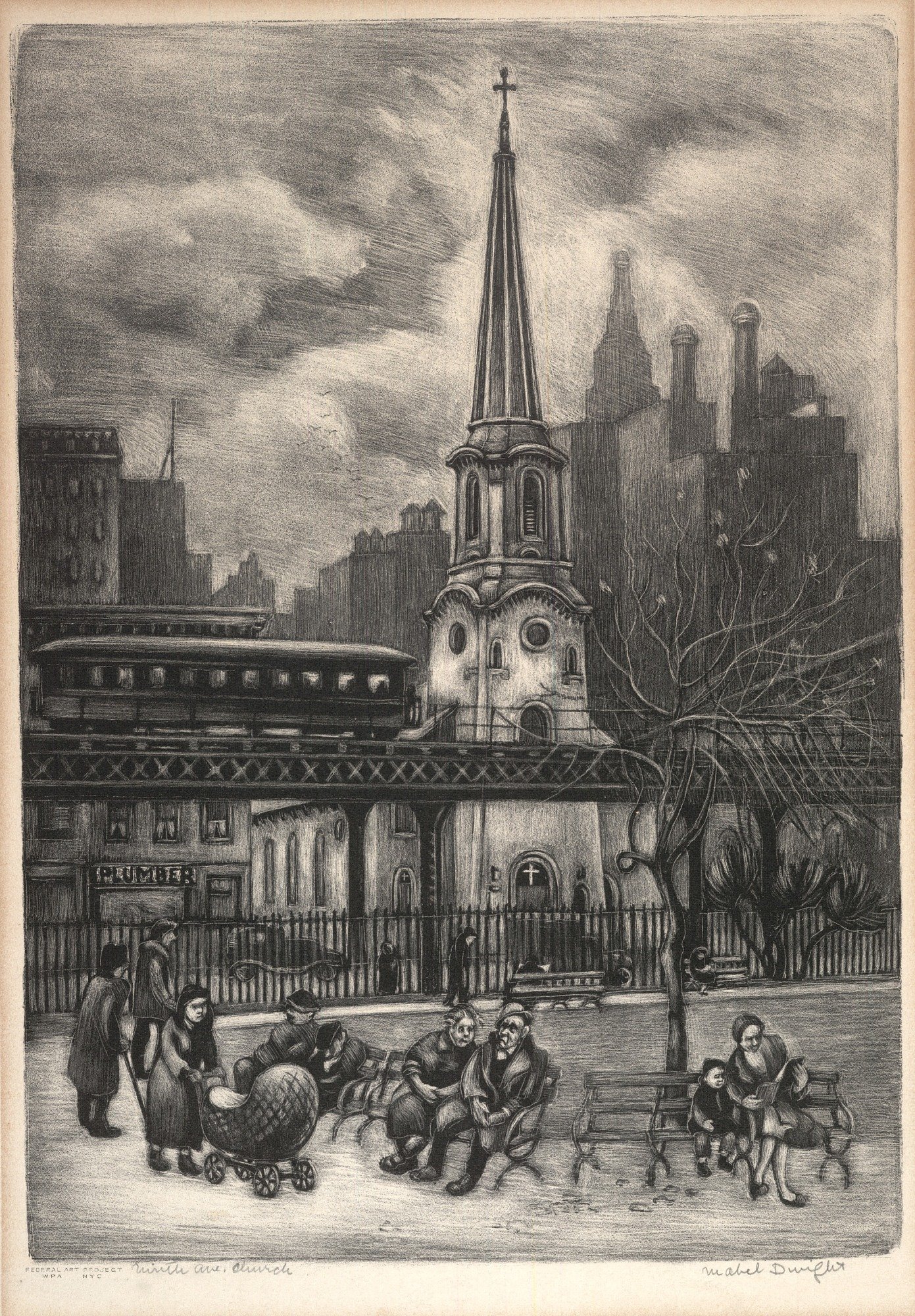

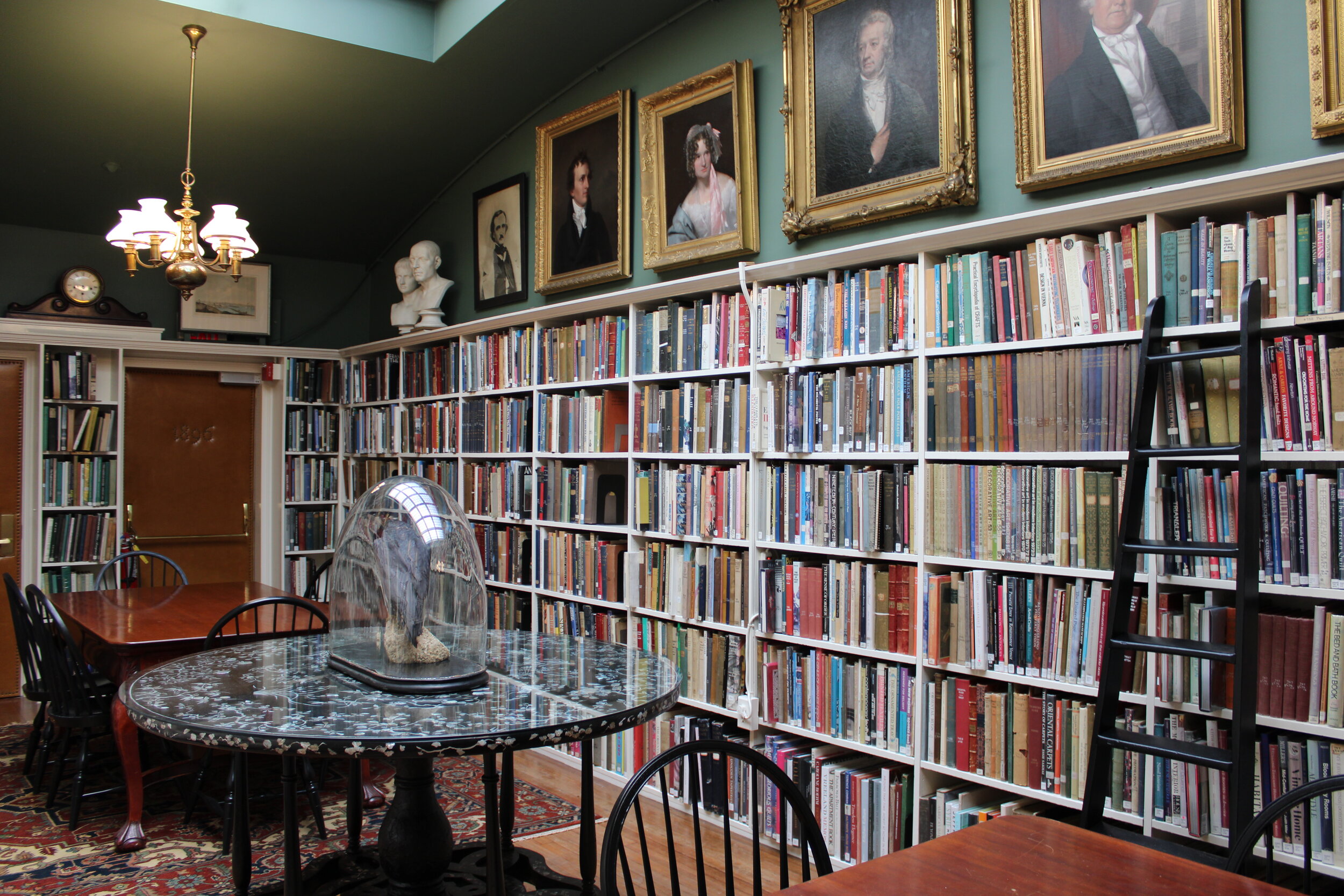

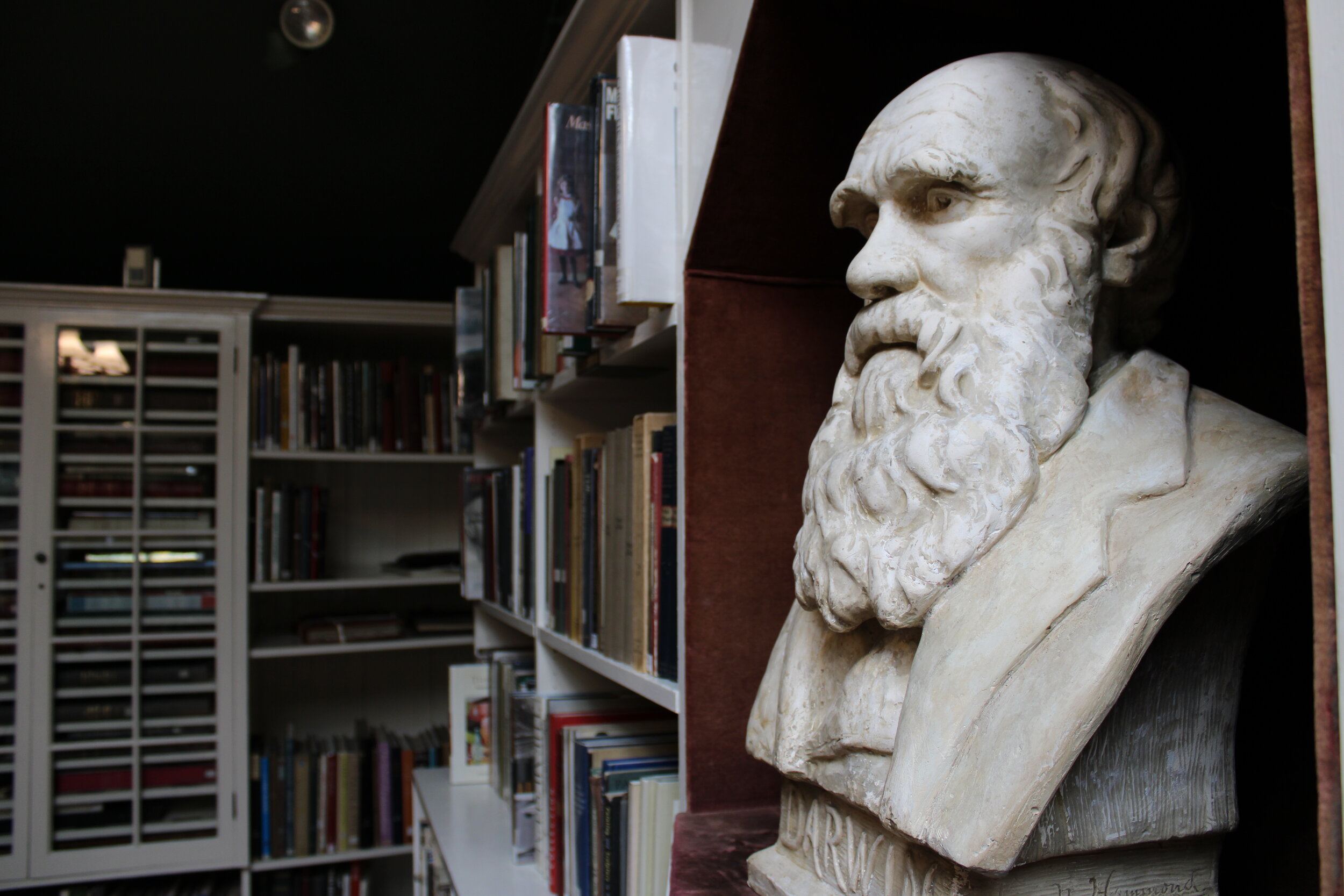

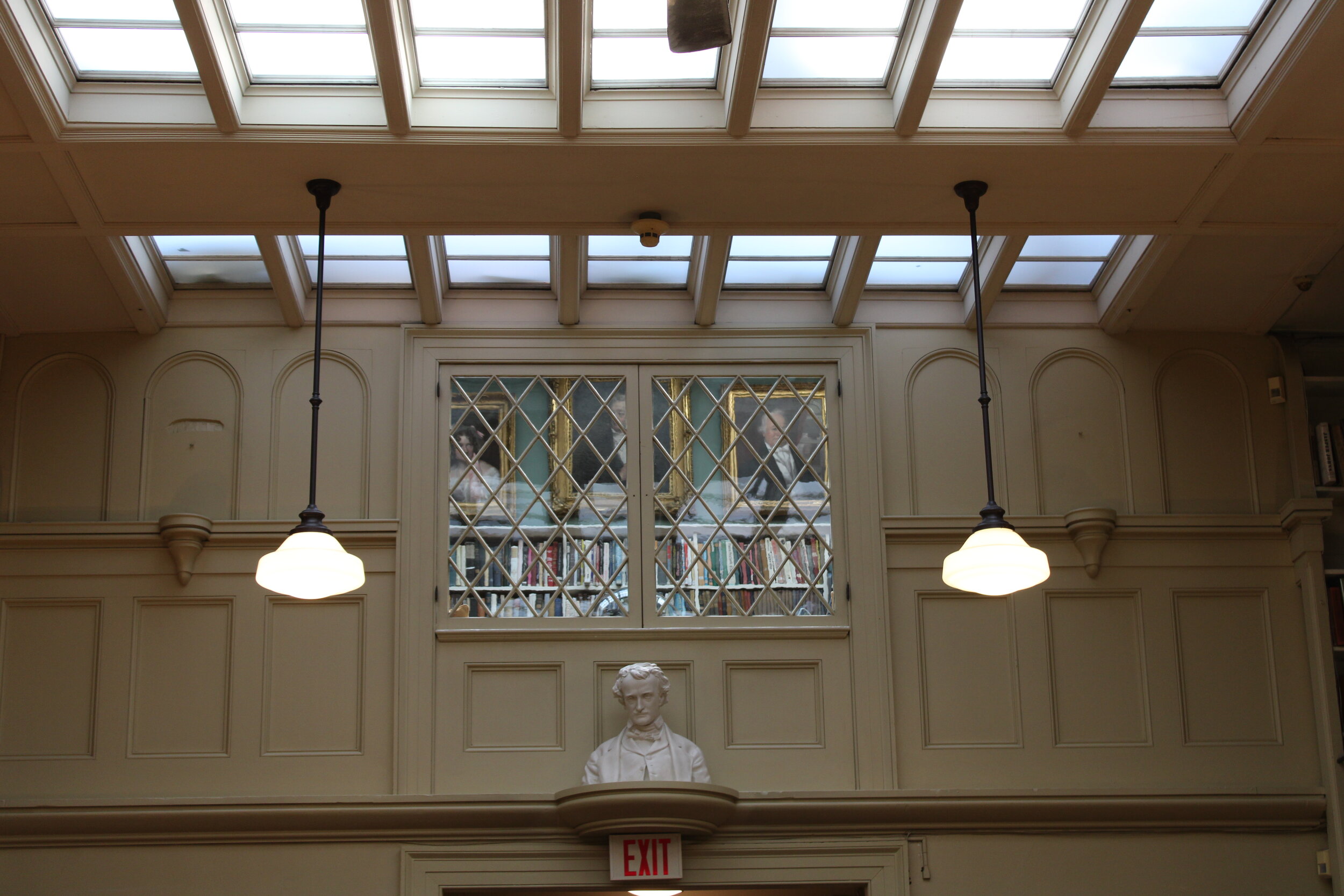

Bringley’s descriptions of some of his favorite artworks from The Met are both precise and extravagant. He is able to weave stories about art and artists with experience and aesthetic impact in a book that becomes its own tour through the museum and through his decade of working at one of the world’s largest art institutions. In between the author’s entrancing ekphrases, evocative illustrations contributed by Maya McMahon bring artworks to life visually.

Some of Bringley’s anecdotes include details one might expect. For instance, he shares that keeping watch over boisterous crowds during blockbuster shows is challenging work and that standing all day is hard on the body. Other details from his years of observing people and art are more nuanced and share poignant aspects of what it means to look at, and engage with, art. These episodes tend to come from human encounters with visitors, students, art enthusiasts, and co-workers, among others.

Many of the writer’s insights go beyond the galleries of The Met and reveal the inner workings of the museum’s guard corps. Bringley shares personal stories about many of his co-workers, illustrating the rich and vibrant diversity of those with whom he worked at the museum. The book becomes something of an accidental portrait of New York in the process, depicting the city and the institution as the nexus of a beautifully interconnected world with many profound stories to share.

All the Beauty in the World is a pleasurable jaunt and one that encourages its readers to take their time on their next museum visit, whether it be at The Met or elsewhere. Certainly, Bringley had an advantage of being alone in galleries for hours on end as part of his job, but he also brings to the endeavor a keen sensitivity for looking at art and for incisive commentary on how it touched and uplifted his life. In doing so he inspires readers to look closer, see better, and experience more deeply.

All the Beauty in the World was published by Simon and Schuster and is available at popular book sellers as well as through the publisher. For readers in the Providence area interested in supporting local bookstores, Books on the Square is also a great venue for book purchases. Learn more about Patrick Bringley at www.patrickbringley.com.